You Are Reading an Article That Critiques Freud's Theory. Which of the Following Could Be the Title?

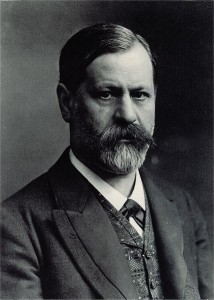

Sigmund Freud (1856—1939)

Sigmund Freud, the begetter of psychoanalysis, was a physiologist, medical physician, psychologist and influential thinker of the early twentieth century. Working initially in close collaboration with Joseph Breuer, Freud elaborated the theory that the listen is a circuitous free energy-organisation, the structural investigation of which is the proper province of psychology. He articulated and refined the concepts of the unconscious, infantile sexuality and repression, and he proposed a tripartite account of the mind's structure—all as part of a radically new conceptual and therapeutic frame of reference for the understanding of human psychological development and the treatment of aberrant mental conditions. All the same the multiple manifestations of psychoanalysis every bit it exists today, it tin in nearly all primal respects be traced directly back to Freud's original piece of work.

Sigmund Freud, the begetter of psychoanalysis, was a physiologist, medical physician, psychologist and influential thinker of the early twentieth century. Working initially in close collaboration with Joseph Breuer, Freud elaborated the theory that the listen is a circuitous free energy-organisation, the structural investigation of which is the proper province of psychology. He articulated and refined the concepts of the unconscious, infantile sexuality and repression, and he proposed a tripartite account of the mind's structure—all as part of a radically new conceptual and therapeutic frame of reference for the understanding of human psychological development and the treatment of aberrant mental conditions. All the same the multiple manifestations of psychoanalysis every bit it exists today, it tin in nearly all primal respects be traced directly back to Freud's original piece of work.

Freud's innovative handling of human actions, dreams, and indeed of cultural artifacts equally invariably possessing implicit symbolic significance has proven to be extraordinarily fruitful, and has had massive implications for a broad variety of fields including psychology, anthropology, semiotics, and artistic creativity and appreciation. Even so, Freud's nigh important and frequently re-iterated claim, that with psychoanalysis he had invented a successful science of the mind, remains the bailiwick of much critical debate and controversy.

Table of Contents

- Life

- Properties to His Thought

- The Theory of the Unconscious

- Infantile Sexuality

- Neuroses and the Structure of the Mind

- Psychoanalysis equally a Therapy

- Critical Evaluation of Freud

- The Merits to Scientific Status

- The Coherence of the Theory

- Freud's Discovery

- The Efficacy of Psychoanalytic Therapy

- References and Farther Reading

- Works by Freud

- Works on Freud and Freudian Psychoanalysis

1. Life

Freud was built-in in Frieberg, Moravia in 1856, merely when he was four years old his family moved to Vienna where he was to alive and work until the last years of his life. In 1938 the Nazis annexed Austria, and Freud, who was Jewish, was allowed to leave for England. For these reasons, it was in a higher place all with the city of Vienna that Freud'south proper name was destined to be deeply associated for posterity, founding as he did what was to go known as the outset Viennese school of psychoanalysis from which flowed psychoanalysis equally a move and all subsequent developments in this field. The telescopic of Freud's interests, and of his professional training, was very broad. He always considered himself first and foremost a scientist, endeavoring to extend the compass of man noesis, and to this terminate (rather than to the practice of medicine) he enrolled at the medical school at the Academy of Vienna in 1873. He concentrated initially on biological science, doing research in physiology for vi years under the great German language scientist Ernst Brücke, who was director of the Physiology Laboratory at the University, and thereafter specializing in neurology. He received his medical degree in 1881, and having become engaged to exist married in 1882, he rather reluctantly took up more secure and financially rewarding work equally a doc at Vienna General Hospital. Shortly later on his marriage in 1886, which was extremely happy and gave Freud six children—the youngest of whom, Anna, was to herself become a distinguished psychoanalyst—Freud set up a individual practice in the handling of psychological disorders, which gave him much of the clinical material that he based his theories and pioneering techniques on.

In 1885-86, Freud spent the greater part of a twelvemonth in Paris, where he was deeply impressed by the piece of work of the French neurologist Jean Charcot who was at that time using hypnotism to treat hysteria and other aberrant mental weather. When he returned to Vienna, Freud experimented with hypnosis merely constitute that its benign furnishings did non final. At this signal he decided to adopt instead a method suggested by the work of an older Viennese colleague and friend, Josef Breuer, who had discovered that when he encouraged a hysterical patient to talk uninhibitedly about the earliest occurrences of the symptoms, they sometimes gradually abated. Working with Breuer, Freud formulated and developed the idea that many neuroses (phobias, hysterical paralysis and pains, some forms of paranoia, then forth) had their origins in deeply traumatic experiences which had occurred in the patient's past simply which were now forgotten—hidden from consciousness. The treatment was to enable the patient to recall the experience to consciousness, to confront it in a deep way both intellectually and emotionally, and in thus discharging it, to remove the underlying psychological causes of the neurotic symptoms. This technique, and the theory from which information technology is derived, was given its classical expression in Studies in Hysteria, jointly published by Freud and Breuer in 1895.

Soon thereafter, all the same, Breuer institute that he could not agree with what he regarded every bit the excessive accent which Freud placed upon the sexual origins and content of neuroses, and the two parted company, with Freud continuing to piece of work alone to develop and refine the theory and practice of psychoanalysis. In 1900, after a protracted period of self-analysis, he published The Interpretation of Dreams, which is by and large regarded equally his greatest piece of work. This was followed in 1901 past The Psychopathology of Everyday Life; and in 1905 by Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality. Freud's psychoanalytic theory was initially not well received—when its existence was acknowledged at all it was usually by people who were, as Breuer had foreseen, scandalized by the emphasis placed on sexuality past Freud. Information technology was not until 1908, when the showtime International Psychoanalytical Congress was held at Salzburg that Freud'southward importance began to exist generally recognized. This was profoundly facilitated in 1909, when he was invited to requite a course of lectures in the United states of america, which were to class the basis of his 1916 book Five Lectures on Psycho-Analysis. From this betoken on Freud'south reputation and fame grew enormously, and he continued to write prolifically until his decease, producing in all more than twenty volumes of theoretical works and clinical studies. He was too not averse to critically revising his views, or to making fundamental alterations to his virtually basic principles when he considered that the scientific prove demanded it—this was well-nigh clearly evidenced by his advancement of a completely new tripartite (id, ego, and super-ego) model of the mind in his 1923 work The Ego and the Id. He was initially greatly heartened by alluring followers of the intellectual caliber of Adler and Jung, and was correspondingly disappointed when they both went on to plant rival schools of psychoanalysis—thus giving rise to the first two of many schisms in the movement—but he knew that such disagreement over basic principles had been part of the early development of every new scientific discipline. After a life of remarkable vigor and artistic productivity, he died of cancer while exiled in England in 1939.

2. Backdrop to His Idea

Although a highly original thinker, Freud was as well deeply influenced by a number of diverse factors which overlapped and interconnected with each other to shape the development of his thought. As indicated above, both Charcot and Breuer had a direct and immediate bear upon upon him, simply some of the other factors, though no less of import than these, were of a rather different nature. First of all, Freud himself was very much a Freudian—his male parent had ii sons by a previous marriage, Emmanuel and Philip, and the young Freud oft played with Philip's son John, who was his own age. Freud'south cocky-analysis, which forms the core of his masterpiece The Interpretation of Dreams, originated in the emotional crunch which he suffered on the death of his male parent and the series of dreams to which this gave rise. This assay revealed to him that the love and admiration which he had felt for his father were mixed with very contrasting feelings of shame and hate (such a mixed attitude he termed ambivalence). Particularly revealing was his discovery that he had often fantasized every bit a youth that his one-half-brother Philip (who was of an age with his mother) was really his father, and certain other signs convinced him of the deep underlying meaning of this fantasy—that he had wished his existent male parent dead because he was his rival for his mother's affections. This was to go the personal (though by no means exclusive) basis for his theory of the Oedipus complex.

Secondly, and at a more general level, account must be taken of the gimmicky scientific climate in which Freud lived and worked. In most respects, the towering scientific effigy of nineteenth century science was Charles Darwin, who had published his revolutionary Origin of Species when Freud was four years old. The evolutionary doctrine radically altered the prevailing conception of man—whereas before, human being had been seen equally a being different in nature from the members of the animal kingdom by virtue of his possession of an immortal soul, he was now seen as being part of the natural order, different from non-human animals merely in caste of structural complexity. This made information technology possible and plausible, for the first time, to care for man every bit an object of scientific investigation, and to excogitate of the vast and varied range of man behavior, and the motivational causes from which it springs, every bit being amenable in principle to scientific caption. Much of the creative work done in a whole diverseness of diverse scientific fields over the next century was to exist inspired past, and derive sustenance from, this new globe-view, which Freud with his enormous esteem for scientific discipline, accustomed implicitly.

An even more than important influence on Freud however, came from the field of physics. The second l years of the nineteenth century saw awe-inspiring advances in contemporary physics, which were largely initiated by the formulation of the principle of the conservation of energy by Helmholz. This principle states, in effect, that the total amount of energy in any given physical organization is e'er constant, that free energy quanta tin exist changed but not annihilated, and that consequently when energy is moved from one part of the arrangement, information technology must reappear in another office. The progressive application of this principle led to awe-inspiring discoveries in the fields of thermodynamics, electromagnetism and nuclear physics which, with their associated technologies, accept so comprehensively transformed the contemporary world. Every bit we take seen, when he offset came to the University of Vienna, Freud worked under the direction of Ernst Brücke who in 1873-four published his Lecture Notes on Physiology (Vorlesungen über Physiologie. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller), setting out the view that all living organisms, including humans, are substantially energy-systems to which, no less than to inanimate objects, the principle of the conservation of free energy applies. Freud, who had great admiration and respect for Brücke, chop-chop adopted this new dynamic physiology with enthusiasm. From there it was merely a short conceptual pace—but ane which Freud was the beginning to take, and on which his merits to fame is largely grounded—to the view that there is such a thing equally psychic energy, that the human personality is also an energy-system, and that it is the role of psychology to investigate the modifications, transmissions and conversions of psychic free energy within the personality which shape and determine it. This latter conception is the very cornerstone of Freud'due south psychoanalytic theory.

3. The Theory of the Unconscious

Freud's theory of the unconscious, then, is highly deterministic—a fact which, given the nature of nineteenth century scientific discipline, should not be surprising. Freud was arguably the first thinker to utilise deterministic principles systematically to the sphere of the mental, and to agree that the broad spectrum of human behavior is explicable merely in terms of the (normally hidden) mental processes or states which determine it. Thus, instead of treating the behavior of the neurotic as being causally inexplicable—which had been the prevailing approach for centuries—Freud insisted, on the contrary, on treating information technology as behavior for which information technology is meaningful to seek an explanation by searching for causes in terms of the mental states of the private concerned. Hence the significance which he attributed to slips of the tongue or pen, obsessive behavior and dreams—all these, he held, are determined by hidden causes in the person's mind, and so they reveal in covert grade what would otherwise non be known at all. This suggests the view that freedom of the will is, if non completely an illusion, certainly more than tightly circumscribed than is unremarkably believed, for information technology follows from this that whenever we brand a option we are governed by hidden mental processes of which nosotros are unaware and over which we have no control.

The postulate that there are such things as unconscious mental states at all is a straight function of Freud'south determinism, his reasoning here being only that the principle of causality requires that such mental states should be, for information technology is axiomatic that there is oft nix in the conscious mind which can be said to crusade neurotic or other behavior. An unconscious mental process or upshot, for Freud, is non one which merely happens to exist out of consciousness at a given time, only is rather one which cannot, except through protracted psychoanalysis, exist brought to the forefront of consciousness. The postulation of such unconscious mental states entails, of course, that the mind is not, and cannot be, either identified with consciousness, or an object of consciousness. To apply a much-used analogy, it is rather structurally akin to an iceberg, the bulk of information technology lying below the surface, exerting a dynamic and determining influence upon the part which is acquiescent to direct inspection—the conscious mind.

Deeply associated with this view of the mind is Freud's account of instincts or drives. Instincts, for Freud, are the principal motivating forces in the mental realm, and as such they energise the mind in all of its functions. There are, he held, an indefinitely big number of such instincts, just these tin can be reduced to a modest number of basic ones, which he grouped into 2 broad generic categories, Eros (the life instinct), which covers all the self-preserving and erotic instincts, and Thanatos (the death instinct), which covers all the instincts towards aggression, self-destruction, and cruelty. Thus it is a error to interpret Freud every bit asserting that all homo actions leap from motivations which are sexual in their origin, since those which derive from Thanatos are non sexually motivated—indeed, Thanatos is the irrational urge to destroy the source of all sexual energy in the annihilation of the cocky. Having said that, it is undeniably true that Freud gave sexual drives an importance and centrality in human life, human actions, and human beliefs which was new (and to many, shocking), arguing as he does that sexual drives be and tin be discerned in children from birth (the theory of infantile sexuality), and that sexual energy (libido) is the single well-nigh important motivating forcefulness in adult life. All the same, a crucial qualification has to be added here—Freud finer redefined the term sexuality to make it cover any course of pleasure which is or can exist derived from the body. Thus his theory of the instincts or drives is essentially that the man being is energized or driven from birth by the desire to acquire and enhance bodily pleasance.

four. Infantile Sexuality

Freud'south theory of infantile sexuality must be seen as an integral office of a broader developmental theory of human personality. This had its origins in, and was a generalization of, Breuer's earlier discovery that traumatic childhood events could have devastating negative effects upon the adult individual, and took the form of the general thesis that early childhood sexual experiences were the crucial factors in the determination of the developed personality. From his business relationship of the instincts or drives it followed that from the moment of nativity the babe is driven in his actions by the desire for actual/sexual pleasure, where this is seen past Freud in nigh mechanical terms as the desire to release mental energy. Initially, infants gain such release, and derive such pleasure, from the human action of sucking. Freud appropriately terms this the oral stage of development. This is followed by a stage in which the locus of pleasance or energy release is the anus, particularly in the act of defecation, and this is accordingly termed the anal phase. And then the immature child develops an interest in its sexual organs as a site of pleasure (the phallic stage), and develops a deep sexual attraction for the parent of the opposite sex, and a hatred of the parent of the same sex (the Oedipus circuitous). This, however, gives rise to (socially derived) feelings of guilt in the child, who recognizes that it can never supplant the stronger parent. A male child also perceives himself to be at risk. He fears that if he persists in pursuing the sexual attraction for his mother, he may be harmed past the father; specifically, he comes to fear that he may be castrated. This is termed castration anxiety. Both the allure for the mother and the hatred are normally repressed, and the child unremarkably resolves the conflict of the Oedipus complex by coming to identify with the parent of the same sex. This happens at the age of 5, whereupon the kid enters a latency menstruum, in which sexual motivations become much less pronounced. This lasts until puberty when mature genital development begins, and the pleasance drive refocuses effectually the genital area.

This, Freud believed, is the sequence or progression implicit in normal man development, and it is to be observed that at the infant level the instinctual attempts to satisfy the pleasure bulldoze are oftentimes checked by parental control and social coercion. The developmental process, and so, is for the child essentially a movement through a series of conflicts, the successful resolution of which is crucial to adult mental health. Many mental illnesses, particularly hysteria, Freud held, can be traced back to unresolved conflicts experienced at this phase, or to events which otherwise disrupt the normal design of infantile development. For case, homosexuality is seen by some Freudians as resulting from a failure to resolve the conflicts of the Oedipus complex, peculiarly a failure to identify with the parent of the aforementioned sex; the obsessive concern with washing and personal hygiene which characterizes the behavior of some neurotics is seen as resulting from unresolved conflicts/repressions occurring at the anal stage.

5. Neuroses and the Structure of the Mind

Freud's account of the unconscious, and the psychoanalytic therapy associated with it, is best illustrated past his famous tripartite model of the structure of the mind or personality (although, as nosotros have seen, he did not formulate this until 1923). This model has many points of similarity with the account of the mind offered past Plato over 2,000 years earlier. The theory is termed tripartite simply considering, once more similar Plato, Freud distinguished 3 structural elements within the heed, which he chosen id, ego, and super-ego. The id is that office of the mind in which are situated the instinctual sexual drives which require satisfaction; the super-ego is that part which contains the censor, namely, socially-acquired control mechanisms which have been internalized, and which are usually imparted in the first instance by the parents; while the ego is the witting self that is created past the dynamic tensions and interactions between the id and the super-ego and has the task of reconciling their conflicting demands with the requirements of external reality. It is in this sense that the listen is to be understood equally a dynamic energy-system. All objects of consciousness reside in the ego; the contents of the id belong permanently to the unconscious mind; while the super-ego is an unconscious screening-mechanism which seeks to limit the bullheaded pleasance-seeking drives of the id by the imposition of restrictive rules. There is some debate as to how literally Freud intended this model to be taken (he appears to have taken it extremely literally himself), merely information technology is of import to annotation that what is being offered here is indeed a theoretical model rather than a description of an appreciable object, which functions as a frame of reference to explain the link betwixt early childhood experience and the mature adult (normal or dysfunctional) personality.

Freud also followed Plato in his account of the nature of mental health or psychological well-being, which he saw as the establishment of a harmonious relationship between the iii elements which constitute the listen. If the external earth offers no scope for the satisfaction of the id's pleasure drives, or more commonly, if the satisfaction of some or all of these drives would indeed transgress the moral sanctions laid down by the super-ego, then an inner conflict occurs in the mind between its elective parts or elements. Failure to resolve this can lead to later neurosis. A key concept introduced here by Freud is that the mind possesses a number of defense mechanisms to endeavor to preclude conflicts from becoming likewise acute, such as repression (pushing conflicts back into the unconscious), sublimation (channeling the sexual drives into the accomplishment socially adequate goals, in art, science, poetry, and and so forth), fixation (the failure to progress beyond one of the developmental stages), and regression (a render to the behavior characteristic of one of the stages).

Of these, repression is the most important, and Freud'south account of this is equally follows: when a person experiences an instinctual impulse to behave in a style which the super-ego deems to exist reprehensible (for example, a strong erotic impulse on the part of the kid towards the parent of the opposite sex), and so it is possible for the listen to push this impulse away, to repress it into the unconscious. Repression is thus one of the central defense mechanisms by which the ego seeks to avoid internal conflict and pain, and to reconcile reality with the demands of both id and super-ego. Every bit such it is completely normal and an integral part of the developmental process through which every child must pass on the style to adulthood. However, the repressed instinctual drive, as an energy-class, is non and cannot be destroyed when information technology is repressed—it continues to exist intact in the unconscious, from where it exerts a determining strength upon the conscious heed, and can give ascent to the dysfunctional behavior characteristic of neuroses. This is one reason why dreams and slips of the natural language possess such a stiff symbolic significance for Freud, and why their assay became such a key part of his treatment—they represent instances in which the vigilance of the super-ego is relaxed, and when the repressed drives are appropriately able to present themselves to the conscious mind in a transmuted course. The difference betwixt normal repression and the kind of repression which results in neurotic illness is one of degree, not of kind—the compulsive behavior of the neurotic is itself a manifestation of an instinctual bulldoze repressed in babyhood. Such behavioral symptoms are highly irrational (and may fifty-fifty be perceived as such by the neurotic), merely are completely beyond the command of the subject field because they are driven past the at present unconscious repressed impulse. Freud positioned the key repressions for both, the normal individual and the neurotic, in the get-go five years of childhood, and of grade, held them to be essentially sexual in nature; since, as we have seen, repressions which disrupt the process of infantile sexual development in particular, according to him, lead to a potent tendency to afterwards neurosis in adult life. The task of psychoanalysis as a therapy is to find the repressions which cause the neurotic symptoms by delving into the unconscious mind of the subject area, and by bringing them to the forefront of consciousness, to allow the ego to confront them straight and thus to discharge them.

6. Psychoanalysis as a Therapy

Freud's account of the sexual genesis and nature of neuroses led him naturally to develop a clinical treatment for treating such disorders. This has become and so influential today that when people speak of psychoanalysis they ofttimes refer exclusively to the clinical treatment; nevertheless, the term properly designates both the clinical treatment and the theory which underlies it. The aim of the method may be stated simply in general terms—to re-plant a harmonious human relationship between the 3 elements which constitute the mind by excavating and resolving unconscious repressed conflicts. The actual method of handling pioneered by Freud grew out of Breuer's earlier discovery, mentioned to a higher place, that when a hysterical patient was encouraged to talk freely almost the earliest occurrences of her symptoms and fantasies, the symptoms began to abate, and were eliminated entirely when she was induced to remember the initial trauma which occasioned them. Turning away from his early attempts to explore the unconscious through hypnosis, Freud further adult this talking cure, acting on the assumption that the repressed conflicts were buried in the deepest recesses of the unconscious listen. Accordingly, he got his patients to relax in a position in which they were deprived of strong sensory stimulation, and even keen sensation of the presence of the analyst (hence the famous utilise of the couch, with the analyst virtually silent and out of sight), and then encouraged them to speak freely and uninhibitedly, preferably without forethought, in the belief that he could thereby discern the unconscious forces lying behind what was said. This is the method of gratis-association, the rationale for which is like to that involved in the analysis of dreams—in both cases the super-ego is to some degree disarmed, its efficiency every bit a screening mechanism is moderated, and material is allowed to filter through to the conscious ego which would otherwise exist completely repressed. The procedure is necessarily a difficult and protracted one, and it is therefore one of the primary tasks of the analyst to help the patient recognize, and overcome, his own natural resistances, which may showroom themselves as hostility towards the analyst. Nonetheless, Freud ever took the occurrence of resistance equally a sign that he was on the right runway in his assessment of the underlying unconscious causes of the patient's condition. The patient'south dreams are of particular interest, for reasons which we take already partly seen. Taking it that the super-ego functioned less effectively in sleep, as in free-association, Freud made a distinction betwixt the manifest content of a dream (what the dream appeared to be about on the surface) and its latent content (the unconscious, repressed desires or wishes which are its real object). The right interpretation of the patient'southward dreams, slips of tongue, free-associations, and responses to carefully selected questions leads the annotator to a indicate where he can locate the unconscious repressions producing the neurotic symptoms, invariably in terms of the patient's passage through the sexual developmental process, the manner in which the conflicts implicit in this process were handled, and the libidinal content of the patient's family unit relationships. To create a cure, the analyst must facilitate the patient himself to become conscious of unresolved conflicts buried in the deep recesses of the unconscious listen, and to confront and engage with them direct.

In this sense, and then, the object of psychoanalytic handling may exist said to be a form of self-understanding—once this is caused information technology is largely up to the patient, in consultation with the analyst, to make up one's mind how he shall handle this newly-acquired understanding of the unconscious forces which motivate him. One possibility, mentioned above, is the channeling of sexual energy into the achievement of social, artistic or scientific goals—this is sublimation, which Freud saw as the motivating force behind near neat cultural achievements. Another possibility would be the witting, rational command of formerly repressed drives—this is suppression. Nonetheless another would exist the conclusion that it is the super-ego and the social constraints which inform information technology that are at fault, in which example the patient may determine in the end to satisfy the instinctual drives. But in all cases the cure is created essentially by a kind of catharsis or purgation—a release of the pent-up psychic energy, the constriction of which was the basic cause of the neurotic illness.

7. Critical Evaluation of Freud

It should be evident from the foregoing why psychoanalysis in general, and Freud in particular, have exerted such a potent influence upon the pop imagination in the Western World, and why both the theory and practice of psychoanalysis should remain the object of a great deal of controversy. In fact, the controversy which exists in relation to Freud is more than heated and multi-faceted than that relating to virtually whatever other mail-1850 thinker (a possible exception being Darwin), with criticisms ranging from the contention that Freud'due south theory was generated by logical confusions arising out of his alleged long-continuing addiction to cocaine (come across Thornton, E.M. Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy) to the view that he made an important, only grim, empirical discovery, which he knowingly suppressed in favour of the theory of the unconscious, knowing that the latter would exist more than socially acceptable (encounter Masson, J. The Assault on Truth).

Information technology should be emphasized hither that Freud's genius is non (generally) in doubt, but the precise nature of his achievement is nevertheless the source of much fence. The supporters and followers of Freud (and Jung and Adler) are noted for the zeal and enthusiasm with which they espouse the doctrines of the main, to the point where many of the detractors of the move encounter it as a kind of secular religion, requiring as it does an initiation process in which the aspiring psychoanalyst must himself first be analyzed. In this manner, it is often alleged, the unquestioning acceptance of a set up of ideological principles becomes a necessary precondition for acceptance into the motion—as with virtually religious groupings. In reply, the exponents and supporters of psychoanalysis oftentimes analyze the motivations of their critics in terms of the very theory which those critics decline. And and then the debate goes on.

Here we will confine ourselves to: (a) the evaluation of Freud'south claim that his theory is a scientific ane, (b) the question of the theory'southward coherence, (c) the dispute concerning what, if annihilation, Freud really discovered, and (d) the question of the efficacy of psychoanalysis as a handling for neurotic illnesses.

a. The Claim to Scientific Status

This is a crucially important consequence since Freud saw himself showtime and foremost as a pioneering scientist, and repeatedly asserted that the significance of psychoanalysis is that it is a new science, incorporating a new scientific method of dealing with the mind and with mental affliction. In that location tin can, moreover, be no dubiousness only that this has been the chief attraction of the theory for nigh of its advocates since and so—on the confront of it, it has the advent of being not just a scientific theory but an enormously strong one, with the chapters to accommodate, and explain, every possible course of human behavior. Nevertheless, it is precisely this latter which, for many commentators, undermines its claim to scientific status. On the question of what makes a theory a genuinely scientific one, Karl Popper's criterion of demarcation, equally information technology is called, has at present gained very general acceptance: namely, that every genuine scientific theory must be testable, and therefore falsifiable, at to the lowest degree in principle. In other words, if a theory is incompatible withpossible observations, it is scientific; conversely, a theory which is compatible with all possible observations is unscientific (run into Popper, Thou. The Logic of Scientific Discovery). Thus the principle of the conservation of energy (physical, not psychic), which influenced Freud so greatly, is a scientific 1 because information technology is falsifiable—the discovery of a physical organization in which the total amount of physical energy was not abiding would conclusively prove it to be false. It is argued that zilch of the kind is possible with respect to Freud's theory—information technology is not falsifiable. If the question is asked: "What does this theory imply which, if false, would show the whole theory to be fake?," the answer is "Nothing" because the theory is compatible with every possible situation. Hence information technology is concluded that the theory is not scientific, and while this does not, as some critics merits, rob it of all value, it certainly diminishes its intellectual status as projected by its strongest advocates, including Freud himself.

b. The Coherence of the Theory

A related (only maybe more serious) point is that the coherence of the theory is, at the very least, questionable. What is attractive well-nigh the theory, even to the layman, is that it seems to offering us long sought-afterward and much needed causal explanations for conditions which take been a source of a great bargain of human being misery. The thesis that neuroses are caused by unconscious conflicts buried deep in the unconscious heed in the form of repressed libidinal energy would appear to offer united states of america, at concluding, an insight in the causal mechanism underlying these aberrant psychological conditions as they are expressed in human behavior, and further testify us how they are related to the psychology of the normal person. Nevertheless, fifty-fifty this is questionable, and is a matter of much dispute. In general, when information technology is said that an consequence X causes another consequence Y to happen, both X and Y are, and must be, independently identifiable. It is true that this is not always a uncomplicated procedure, as in science causes are sometimes unobservable (sub-atomic particles, radio and electromagnetic waves, molecular structures, and so along), but in these latter cases there are articulate correspondence rules connecting the unobservable causes with observable phenomena. The difficulty with Freud'southward theory is that it offers us entities (for example repressed unconscious conflicts), which are said to be the unobservable causes of certain forms of beliefs Merely there are no correspondence rules for these alleged causes—they cannot be identified except by reference to the behavior which they are said to cause (that is, the analyst does not demonstratively assert: "This is the unconscious cause, and that is its behavioral consequence;" rather he asserts: "This is the beliefs, therefore its unconscious crusade must exist"), and this does raise serious doubts as to whether Freud's theory offers us genuine causal explanations at all.

c. Freud'southward Discovery

At a less theoretical, but no less critical level, information technology has been alleged that Freud did make a genuine discovery which he was initially prepared to reveal to the world. Withal, the response he encountered was so ferociously hostile that he masked his findings and offered his theory of the unconscious in its place (meet Masson, J. The Assault on Truth). What he discovered, it has been suggested, was the extreme prevalence of kid sexual abuse, especially of young girls (the vast bulk of hysterics are women), even in respectable nineteenth century Vienna. He did in fact offer an early on seduction theory of neuroses, which met with trigger-happy animosity, and which he chop-chop withdrew and replaced with the theory of the unconscious. As 1 contemporary Freudian commentator explains it, Freud'south change of mind on this result came about as follows:

Questions concerning the traumas suffered past his patients seemed to reveal [to Freud] that Viennese girls were extraordinarily frequently seduced in very early childhood by older male relatives. Doubt about the bodily occurrence of these seductions was soon replaced by certainty that it was descriptions about childhood fantasy that were being offered. (MacIntyre).

In this style, it is suggested, the theory of the Oedipus circuitous was generated.

This argument begs a number of questions, non to the lowest degree, what does the expression extraordinarily often hateful in this context? By what standard is this being judged? The reply can only be: By the standard of what we generally believe—or would similar to believe—to exist the case. But the contention of some of Freud'southward critics here is that his patients were not recalling babyhood fantasies, but traumatic events from their babyhood which were all also real. Freud, according to them, had stumbled upon and knowingly suppressed the fact that the level of child sexual abuse in society is much higher than is more often than not believed or best-selling. If this contention is truthful—and it must at least exist contemplated seriously—then this is undoubtedly the most serious criticism that Freud and his followers have to face.

Further, this particular point has taken on an added and even more controversial significance in recent years, with the willingness of some contemporary Freudians to combine the theory of repression with an acceptance of the wide-spread social prevalence of child sexual abuse. The result has been that in the United states of america and Uk in particular, many thousands of people have emerged from analysis with recovered memories of declared babyhood sexual abuse by their parents; memories which, it is suggested, were hitherto repressed. On this basis, parents have been defendant and repudiated, and whole families have been divided or destroyed. Unsurprisingly, this in turn has given ascent to a systematic backlash in which organizations of accused parents, seeing themselves every bit the true victims of what they term False Retentiveness Syndrome, have denounced all such memory-claims as falsidical — the direct product of a belief in what they see as the myth of repression. (run into Pendergast, M. Victims of Memory). In this mode, the concept of repression, which Freud himself termed the foundation stone upon which the structure of psychoanalysis rests, has come in for more widespread disquisitional scrutiny than ever before. Here, the fact that, different some of his contemporary followers, Freud did not himself always eyebrow the extension of the concept of repression to embrace bodily child sexual abuse, and the fact that nosotros are not necessarily forced to choose between the views that all recovered memories are either veridical or falsidical are often lost sight of in the extreme heat generated by this debate, possibly understandably.

d. The Efficacy of Psychoanalytic Therapy

Information technology does not follow that, if Freud's theory is unscientific, or even false, it cannot provide us with a basis for the beneficial treatment of neurotic disease because the relationship between a theory's truth or falsity and its utility-value is far from being an isomorphic i. The theory upon which the use of leeches to bleed patients in eighteenth century medicine was based was quite spurious, just patients did sometimes actually do good from the treatment! And of form even a true theory might be badly applied, leading to negative consequences. 1 of the problems here is that it is difficult to specify what counts equally a cure for a neurotic illness as singled-out, say, from a mere alleviation of the symptoms. In general, however, the efficiency of a given method of treatment is usually clinically measured past ways of a control grouping—the proportion of patients suffering from a given disorder who are cured by treatment Ten is measured by comparing with those cured past other treatments, or by no treatment at all. Such clinical tests as have been conducted indicate that the proportion of patients who take benefited from psychoanalytic treatment does not diverge significantly from the proportion who recover spontaneously or as a result of other forms of intervention in the control groups used. So, the question of the therapeutic effectiveness of psychoanalysis remains an open up and controversial one.

8. References and Further Reading

a. Works by Freud

- The Standard Edition of the Consummate Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud (Ed. J. Strachey with Anna Freud), 24 vols. London: 1953-1964.

b. Works on Freudand Freudian Psychoanalysis

- Abramson, J.B. Liberation and Its Limits: The Moral and Political Idea of Freud. New York: Free Press, 1984.

- Bettlelheim, B. Freud and Man's Soul. Knopf, 1982.

- Cavell, K. The Psychoanalytic Mind: From Freud to Philosophy. Harvard University Press, 1993.

- Cavell, M. Condign a Discipline: Reflections in Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Chessick, R.D. Freud Teaches Psychotherapy. Hackett Publishing Company, 1980.

- Cioffi, F. (ed.) Freud: Modern Judgements. Macmillan, 1973.

- Deigh, J. The Sources of Moral Bureau: Essays in Moral Psychology and Freudian Theory. Cambridge, United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland: Cambridge Academy Press, 1996.

- Dilman, I. Freud and Human Nature. Blackwell, 1983

- Dilman, I. Freud and the Mind. Blackwell, 1984.

- Edelson, M. Hypothesis and Prove in Psychoanalysis. University of Chicago Printing, 1984.

- Erwin, E. A Last Accounting: Philosophical and Empirical Bug in Freudian Psychology. MIT Press, 1996.

- Fancher, R. Psychoanalytic Psychology: The Development of Freud's Thought. Norton, 1973.

- Farrell, B.A. The Continuing of Psychoanalysis. Oxford University Press, 1981.

- Fingarette, H. The Self in Transformation: Psychoanalysis, Philosophy, and the Life of the Spirit. HarperCollins, 1977.

- Freeman, L. The Story of Anna O.—The Woman who led Freud to Psychoanalysis. Paragon House, 1990.

- Frosh, S. The Politics of Psychoanalysis: An Introduction to Freudian and Mail-Freudian Theory. Yale University Press, 1987.

- Gardner, S. Irrationality and the Philosophy of Psychoanalysis. Cambridge, Cambridge Academy Press, 1993.

- Grünbaum, A. The Foundations of Psychoanalysis: A Philosophical Critique. Academy of California Press, 1984.

- Gay, V.P. Freud on Sublimation: Reconsiderations. Albany, NY: State University Press, 1992.

- Claw, Due south. (ed.) Psychoanalysis, Scientific Method, and Philosophy. New York University Printing, 1959.

- Jones, E. Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (three vols), Basic Books, 1953-1957.

- Klein, Thousand.South. Psychoanalytic Theory: An Exploration of Essentials. International Universities Press, 1976.

- Lear, J. Love and Its Identify in Nature: A Philosophical Interpretation of Freudian Psychoanalysis. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1990.

- Lear, J. Open up Minded: Working Out the Logic of the Soul. Cambridge, Harvard Academy Press, 1998.

- Lear, Jonathan. Happiness, Death, and the Residuum of Life. Harvard Academy Press, 2000.

- Lear, Jonathan. Freud. Routledge, 2005.

- Levine, M.P. (ed). The Analytic Freud: Philosophy and Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Levy, D. Freud Among the Philosophers: The Psychoanalytic Unconscious and Its Philosophical Critics. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996.

- MacIntyre, A.C. The Unconscious: A Conceptual Analysis. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1958.

- Mahony, P.J. Freud'south Dora: A Psychoanalytic, Historical and Textual Study. Yale University Press, 1996.

- Masson, J. The Attack on Truth: Freud's Suppression of the Seduction Theory. Faber & Faber, 1984.

- Neu, J. (ed). The Cambridge Companion to Freud. Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- O'Neill, J. (ed). Freud and the Passions. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004.

- Popper, Grand. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson, 1959.

- Pendergast, Grand. Victims of Memory. HarperCollins, 1997.

- Reiser, K. Listen, Encephalon, Body: Towards a Convergence of Psychoanalysis and Neurobiology. Basic Books, 1984.

- Ricoeur, P. Freud and Philosophy: An Essay in Interpretation (trans. D. Savage). Yale University Press, 1970.

- Robinson, P. Freud and His Critics. Berkeley, University of California Press, 1993.

- Rose, J. On Not Existence Able to Slumber: Psychoanalysis and the Modern World. Princeton University Press, 2003.

- Roth, P. The Superego. Icon Books, 2001.

- Rudnytsky, P.L. Freud and Oedipus. Columbia University Press, 1987.

- Said, E.W. Freud and the Non-European. Verso (in association with the Freud Museum, London), 2003.

- Schafer, R. A New Language for Psychoanalysis. Yale University Press, 1976.

- Sherwood, M. The Logic of Explanation in Psychoanalysis. Bookish Press, 1969.

- Smith, D.Fifty. Freud's Philosophy of the Unconscious. Kluwer, 1999.

- Stewart, W. Psychoanalysis: The Outset 10 Years, 1888-1898. Macmillan, 1969.

- Sulloway, F. Freud, Biologist of the Mind. Basic Books, 1979.

- Thornton, E.G. Freud and Cocaine: The Freudian Fallacy. Blond & Briggs, 1983.

- Tauber, A.I. Freud, the Reluctant Philosopher. Princeton Academy Press, 2010.

- Wallace, East.R. Freud and Anthropology: A History and Reappraisal. International Universities Printing, 1983.

- Wallwork, E. Psychoanalysis and Ethics. Yale University Press, 1991.

- Whitebrook, J. Perversion and Utopia: A Written report in Psychoanalysis and Critical Theory. MIT Press, 1995.

- Whyte, L.L. The Unconscious Before Freud. Basic Books, 1960.

- Wollheim, R. Freud. Fontana, 1971.

- Wollheim, R. (ed.) Freud: A Collection of Disquisitional Essays. Anchor, 1974.

- Wollheim, R. & Hopkins, J. (eds.) Philosophical Essays on Freud. Cambridge University Printing, 1982.

See as well the manufactures on Descartes' Listen-Body Distinction, Higher-Order Theories of Consciousness and Introspection.

Author Data

Stephen P. Thornton

Email: stephen.thornton@mic.ul.ie

University of Limerick

Republic of ireland

Source: https://iep.utm.edu/freud/

0 Response to "You Are Reading an Article That Critiques Freud's Theory. Which of the Following Could Be the Title?"

Postar um comentário